Ecological Lessons From Studio Ghibli Films

Effective ways Hayao Miyazaki depicts and portrays environmentalism and appreciating the beauty of nature.

Different fields of science such as sustainability, ecological economics, ecology, etc. can range from the ‘big picture to narrowed down areas of interest. Scientists studying the environment often present their findings to various audiences such as academics, government, businesses, and the general public (1). Unfortunately, most of these fields rely solely on scientific journals or books to report their findings to the general public, which may not be digestible. Alternative forms of media such as films are often underutilized to explain and emphasize messages on ecological topics (1). Films can address various issues, from air and water pollution to toxic waste, overpopulation, sustainability, biodiversity loss, and climate change, and investigate complex questions such as optimal economic scale and intergenerational and inter-species equity (1).

While many films out there target specialized audiences, these films often aren’t as digestible for broader audiences who may not be familiar with such intensive fields of science and may not influence the way they think or view their role in the ecosystem (1). Hayao Miyazaki, a Japanese animator, film director, and storyteller, applies bultural and ethical dimensions to his films, presenting a clear message on complex ecological and societal issues (1). Miyazaki best explains how he addresses his ecological views in his movies in his own words:

“I think it better to think of environmental problems in view of ‘courtesy’... we need courtesy toward water, mountains, and air in addition to living things. We should not ask courtesy from these things, but we ourselves should give courtesy toward them instead. I do believe the existence of the period when the ‘power’ of forests was much stronger than our power. There is something missing within our attitude toward nature” (1).

Five films in particular best discuss his views on ecology and consumption.

Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind (1984)

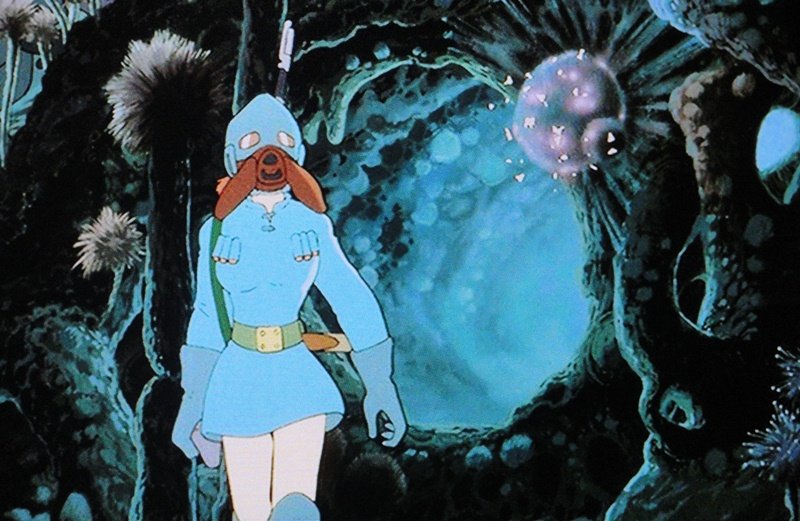

The film tells the story of our main character Nausicaä, living in a world after a major post-apocalyptic conflict devastating the majority of the planet’s ecosystem, with only a few human societies living across environments that have become “toxic jungles” (2). The surviving human settlements fear the forest and wish to destroy it, without recognizing the toxic jungle and the dangerous insects within it are cleaning and restoring the environment (2). Many people avoid going into the jungle becauseit is filled with dangerous creatures such as the Ohmu, and poisonous spores. Nausicaä regularly explores the jungle and collects the toxic spores to grow them under the palace to clean the soil and water (2). Throughout the film she discovers the only way humans can have an optimistic future is to let nature purify what they have polluted and degraded (3). Nausicaä works hard throughout the film to bring peace back to the damaged planet.

Miyazaki designed the film to mirror modern society’s view on the short-term materialistic gain being prioritized mores than long-term environmental sustainability, which can result in massive ecological collapse (2). The film consistently reminds us that being in constant conflict with nature will ultimately end in our own demise, and that we must create a more sustainable future working and connecting with nature rather than exploiting and fighting against it (2). The strained relationship between the humans and nature illustrates what the world might possibly exist after the collapse of our industrial society (3). We see this disconnect from nature in modern society due to the overcrowding and struggles to exist under the pressures of capitalism, primarily in urbanized or heavily developed areas (3). Lastly, the film calls on audiences to reach out and find connections to the natural world, and understand how much society still stands to lose if it continues down its current path (3).

My Neighbor Totoro (1988)

A pair of young sisters move to a new house in the countryside with their father as their mother recovers from an illness (2). The girls explore their new house and surroudning forest and meet Totoro and develop a friendship with him and discover their love for their environment (2). Totoro is depicted as a warm and nurturing figure representing the healing effects of interacting with nature (2). Totoro is a character designed to be a giant forest spirit without any emotion (5). Totorois the forest spirit who protects and keeps the forest safe and far away from danger (5).

This film is specifically targeted towards children. My neighbor totoro is a letter to Miyazaki and his own childhood (1). Miyazaki holds a deep love for the plants as a symbol of complexity and diversity (1). Totoro is a giant forest spirit that looks like a huge bunny rabbit, he decided that the forest spirit must not have a heavily animated face to might reveal what it is thinking. Totoro’s existence, even without literal interaction with it has significant meaning and warm feelings for us all (1). Miyazaki didn’t create the animation because of his nostalgia about landscapes of the 1940s and early 50s, but rather he wishes that the movie inspires children to explore and venture out into the forest and discover the fascination of plants, similarly as the sisters do in the movie. Miyazaki wanted to encourage young children to discover their love of nature by running through it, similarly to Mei and Satsuki (5). Miyazaki hopes that children would grow up to be like Totoro who would preserve their environment when it was threatened (5). He urges younger audiences to replicate what Mei, Satsuki, and Totoro do and pick up acorns and replant them to demonstrate how valuable and vital nature is to humans (5).

Princess Mononoke (1997)

Princess Mononoke is set in 14th century Japan, in a world that is in conflict between humans and the forest spirits leads to casualties on both sides (2). Princess Mononoke (called San) is a girl raised by wolves and develops a hatred toward human society. San is a human raised by a wolf goddess fighting to protect the forest spirit, and lady Eboshi the leader of Irontown (4). Ashitaka, our other main character is cursed by the boar god after he is shot by Lady Eboshi (1). Lady Eboshi, the leader of the Irontown, encounters the boar god due to her responsibility for forest destruction and shoots the wild boar god who is considered the guardian of the forest, and changes into a demon because of rage and fear (1). Ashitaka is banished from his tribe due to his deadly curse, and finds his way to the mine (1). Lady Eboshi is not a clearcut villain, although she wants to cut down the forest to feed the iron mines, she is also kind and generous as a leader who provides a sanctuary for social outcasts and encourages gender equality (2). Although her desire to build a better society, her actions will destroy the forest and the homes of the kami even if her goals are well-intentioned (2). This situation within the film is a well-known topic in ongoing environmental justice issues across the world, in which poor and marginalized groups suffer for the actions of the wealthy (2). Miyazaki depicts and encourages audiences to move beyond the mindset of “us versus them” which allows groups with more power to distance themselves from those without and dehumanize these groups altogether (2).

Human greed and the disregard for nature are at the heart of many issues within this film and is the result of Ashitaka’s curse (3). The soldiers of Irontown along with their leader, Lady Eboshi shot and killed the boar god, Nago, who protected the mountain they were attempting to extract iron ore from (3). The boar’s anger towards humans festers inside Ashitaka after he was attacked by Nago after his death (3). Ashitaka learns valuable lessons throughout the film on the future of the natural world and humankind and understands that humans must live in harmony with nature and the spirits that protect it, to healthfully move forward and thrive together (3). The actions of Irontown helped them industrialize but it results in pollution, depletion of resources, and conflict with the gods (3). With humans, nature, and the gods imbalanced the humans fear that they will lose their place and power in the forest and the same is believed by the forest gods in regard to humans (3).

The film explains that the shishigami is the guardian of the forest. In Shinto belief, kami are spirits that are a part of nature but are not soft-natured entities, when humans refuse to respect their environment they can seek revenge (2). The most powerful kami is the Forest Spirit (Shishigami) who is neither good nor evil but represents the pure power of nature (2). Shishigami appears as a deer during the day, but turns into a nightwalker at night, the transformation represents the duality of nature as a bringer of life and death (2). This message echoes how the natural world has the ability to both support and destroy humankind (2).

San and the wolf goddess defend the forest and try to persuade to boar tribe from going to war with Irontown. The need to protect her people and help her village grow and thrive, results in Lady Eboshi intending to kill the forest spirit. After she beheads the Shishigami, the body becomes a large toxic mass that destroys everything it touches (3). Ashitaka and San attempt to return the head and are successful, resulting in Shishigami’s body scattering across the forest and purifying the war and hatred amongst the gods and humans (3). Purification is an important factor in Shinto ideology, as it respects the spirits and the natural world they inhabit (3). Of course, conflict arises in the climax and in the nick of time avoids catastrophe after recognizing the importance to live in harmony between humans and nature (4).

Princess Mononoke calls to action for humanity to examine the way in which we interact with the natural world and remind the audience that the relationship between humans and nature is reciprocal (3). Nature and humans can help one another, but can also destroy one another (3).

Spirited Away (2001)

Spirited Away is the best-known film by Miyazaki and has received numerous accolades for its imaginative characters and depictions of complex themes (1). The main focus is on the misadventures of Chihiro who was separated from her parents after they eat the food of the spirits and are turned into pigs (1). Miyazaki introduces ecological elements subtly but with important subtext throughout the film (1). For instance, at the beginning of the film, Chihiro and her parents pass through an abandoned amusement park and acknowledge that the river passing through the park dried up, and all of the area surrounding the park is developed (1). She ends up in a bathhouse in the spirit world, and through her hard work and determination, she is able to find a way to rescue her parents who had fallen victim to irresponsible consumption (1).

The environmental messages become clearer when Chihiro encounters two strangers in the bathhouse (1). First, she is asked by Yubaba, the owner of the bathhouse, to care for a stink spirit that seeks help and cleansing (1). Due to its appearance and stench, it is first turned away from the bathhouse because it scares off the guests and staff (1). It is only welcomed in because of its great wealth (1). As Chihiro tends to the stink spirit, the spirit shows her a bicycle handle poking out of its side, leading to a discovery of an immense amount of garbage and pollution (1). The spirit, after being cleansed and cared for emerges as a river spirit, whose identity was lost because the real river it protected was filled for housing development (1). The message of human greed for non-material things is also depicted in No Face, another spirit that appears to be wealthy and gluttonous (1). No Face tries to win over Chihiro’s friendship with gold and other items gifted to him in the bathhouse by other employees who want his gold, but her lack of interest in his offerings conflicts with his aim to win her over (1).

When you initially watch, it’s not clear that the movie provides an environmental message to the audience, but looking closely, the stink spirit serves as a subtle reminder for us to be conscious of our surroundings and activities that may harm the environment (5).

Ponyo (2008)

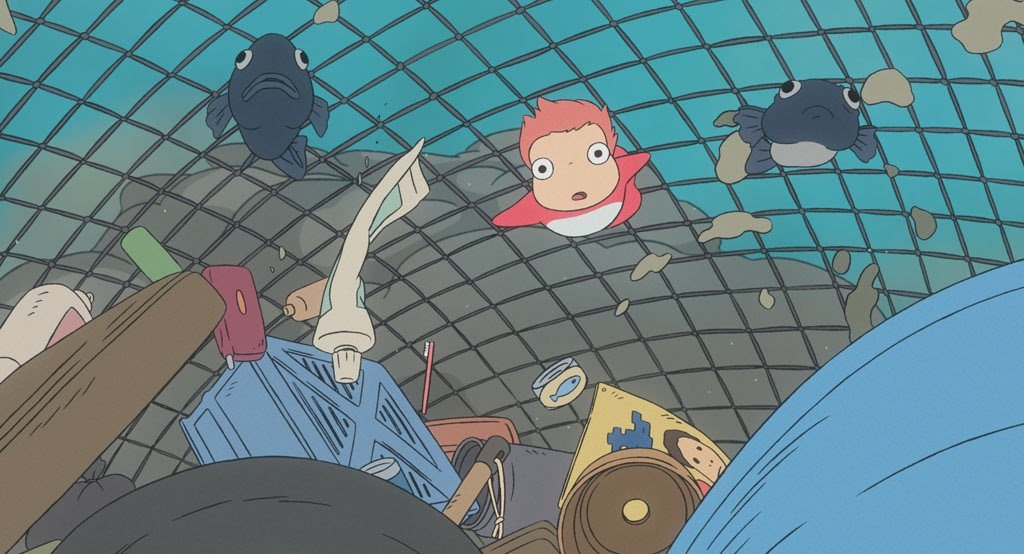

The film tells the story of Ponyo, a goldfish princess who encounters a human boy named Sosuke, who giver her the name Ponyo. Ponyo wants to become human, and as her friendship with Sosuke develops, she becomes more humanlike. Ponyo’s father, Fujimoto, is a masterful wizard who attempts to bring her back to the sea, but she uses her father’s magic to transform herself into a human, but the powerful magic can cause imbalance in the world and results in massive environmental changes and severe weather events in Sosuke’s town. It is up to Ponyo to help her friend and the town from returning to the sea.

The film is similar to My Neighbor Totoro in terms of the childlike experience, but the film still portrays signals of environmental concern (6). The ocean is depicted as heavily polluted, in one scene a fishing boat is shown hauling trawling nets up, catching more trash than fish (6). Or when Fujimoto creates water blobs that help him try to catch Ponyo, we see the blobs move through empty bottles of plastic (6). Fujimoto despises humans for what they have done to the ocean and their greediness (6). Although the movie primarily focuses on the relationship between Sosuke and Ponyo, the environmental message is clear in this film, that the world’s natural balance needs to be respected (7). Throughout the film we see contrasts between beautiful and ancient sea creatures of the ocean, and the ugliness of pollution from humans (7).

References:

Mayumi, Kozo, et al. “The Ecological and Consumption Themes of the Films of Hayao Miyazaki.” Ecological Economics, vol. 54, no. 1, 2005, pp. 1–7., https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2005.03.012.

Rawlins, Aimee. “These Visually Striking Films Will Help You Rediscover the Wonder of Nature.” Fast Company, Fast Company, 1 May 2022, https://www.fastcompany.com/90747539/these-visually-striking-films-will-help-you-rediscover-the-wonder-of-nature.

Sethares, Lileana. “The Environmental Relevance of Studio Ghibli Films • The Daily Fandom.” The Daily Fandom, https://thedailyfandom.org/environmental-relevance-of-studio-ghibli-films/.

Harter, Theresa-Anne Clarke. “Princess Mononoke and Our Environmental Relationship.” The New Twenties, The New Twenties, 27 Aug. 2020, https://thenewtwenties.ca/articles/princessmononoke.

Lee, Jihyun. “The Environmental Messages in Miyazaki's Studio Ghibli Movies.” Japan Nakama, 6 May 2022, https://www.japannakama.co.uk/the-environmental-messages-in-miyazakis-studio-ghibli-movies/.

Morris, Wesley. “Ponyo - Stuff of Dreams Mixed with a Green Message.” Boston.com, The Boston Globe, 14 Aug. 2009, http://archive.boston.com/lifestyle/family/articles/2009/08/14/ponyo_integrates_stuff_of_dreams_with_an_ecological_message/.