Is Palm Oil Sustainable?

The Environmental Impact of Palm Oil

What exactly is palm oil?

The African oil palm (Elaieis guineensis), native to West and Central Africa, is a globally used plant and is the leading vegetable oil source for food, cosmetics, and biofuel in today’s market (1). Oil palms are a more sought-after plant in terms of vegetable oil-related crops due to their ability to quickly adapt to various growing conditions without reducing the crop output or stressing the plant altogether (1). In recent years, the amount being utilized or consumed by the general public has dramatically increased due to its versatility in various products and increased demand for vegetable oil (1, 2). Two palm oil forms can be processed: crude palm oil and palm kernel oil (4). Crude palm oil is processed by crushing the fleshy body, or the fruit, to extract the refined oil, whereas palm kernel oil involves crushing up the pit inside of the fruit (4). Oil palms are grown on a wide variety of soil types within monoculture plantations, which vary in size and intensity from individual smallholdings to more significant private estates that expand over 20,000 ha in the area (5). These more extensive privatized plantations make up half of Indonesia’s production compared to smallholdings only accounting for 35% (5). The global economic value of crude palm oil in 2007 was over US$ 900 but has risen to US$ 4,790 in 2021 (7, 8). The global consumer demand for palm oil in 2016 was 59,378 metric tonnes to a recent increase in 2021 of 75,453 metric tonnes annually (9). There is a projected increase in demand for palm oil by 46% by 2050 (6).

There is extensive research on the processing methods and analyzing the entire life cycle of palm oil production. By utilizing evaluation methods such as The Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) to determine the environmental impact, explaining what is produced at each stage of the product’s life cycle and what is specifically being used in terms of raw materials (i.e., water, energy, fertilizers, pesticides, etc.) as well as what is being emitted (i.e., air and water pollution, land degradation, gas emissions, etc.) (3). Compared to other oil crops, palm oil has the lowest production costs and land usage, making it highly valuable for both companies and countries (7). Although the methods to produce palm oil or palm kernel oil are believed to create less impact overall to the environment, due to its life cycle assessment, compared to other intensive or nutrient-demanding vegetable oil crops (1,2). The environmental effects far outweigh the benefits to less demanding crops and slight socioeconomic benefits due to the adverse effects on the environment through increased deforestation and carbon emissions.

What’s so bad about palm oil?

Over 3 billion people within 150 countries consume products that contain palm oil, with an average consumption rate of 8 kg (approximately 17.6 lbs) of palm oil per year (10). The majority of palm oil produced and exported globally comes from Malaysia and Indonesia, which helps support local income (in terms of smallholdings) and detrimental costs to the environment (10). Although palm oil benefits socioeconomic health, the financial incentives to intensively produce palm oil leads to a massive increase in greenhouse gas emissions due to deforestation via slash-and-burn methods (10). The unfortunate part is that people are often unaware of what palm oil exactly is or are deceived by companies that claim to create products with sustainable palm oil. The continued global demand for palm oil poses threats to biodiversity in tropical regions, increased air pollution, and degraded ecosystems. The most commonly associated threat and or concern with palm oil production is the decline of the world’s three remaining orangutan species.

Palm oil plantations, both smallholding and private company estates globally, use 40.6 million acres (16.4 million hectares) (2). To put this into perspective, the total land use equates to the size of the state of Georgia in the US (2). Interest in growing palm oil has spread to other tropical countries, which leads to potential risks of increased development and removal of tropical ecosystems (2). Tropical rainforests contain large quantities of carbon in old-growth and regenerating and or disturbed forests (2). When these rainforests are removed to continue palm oil plantation development, carbon dioxide is released into the atmosphere, accounting for 10% of total global warming emissions (2). Palm oil cultivation within Indonesia accounted for approximately 2-9% of land-use emissions from 2000 to 2010, is considered the seventh-largest emitter of global warming-related pollution in 2009, and deforestation accounting for about 30% of emissions as well (2).

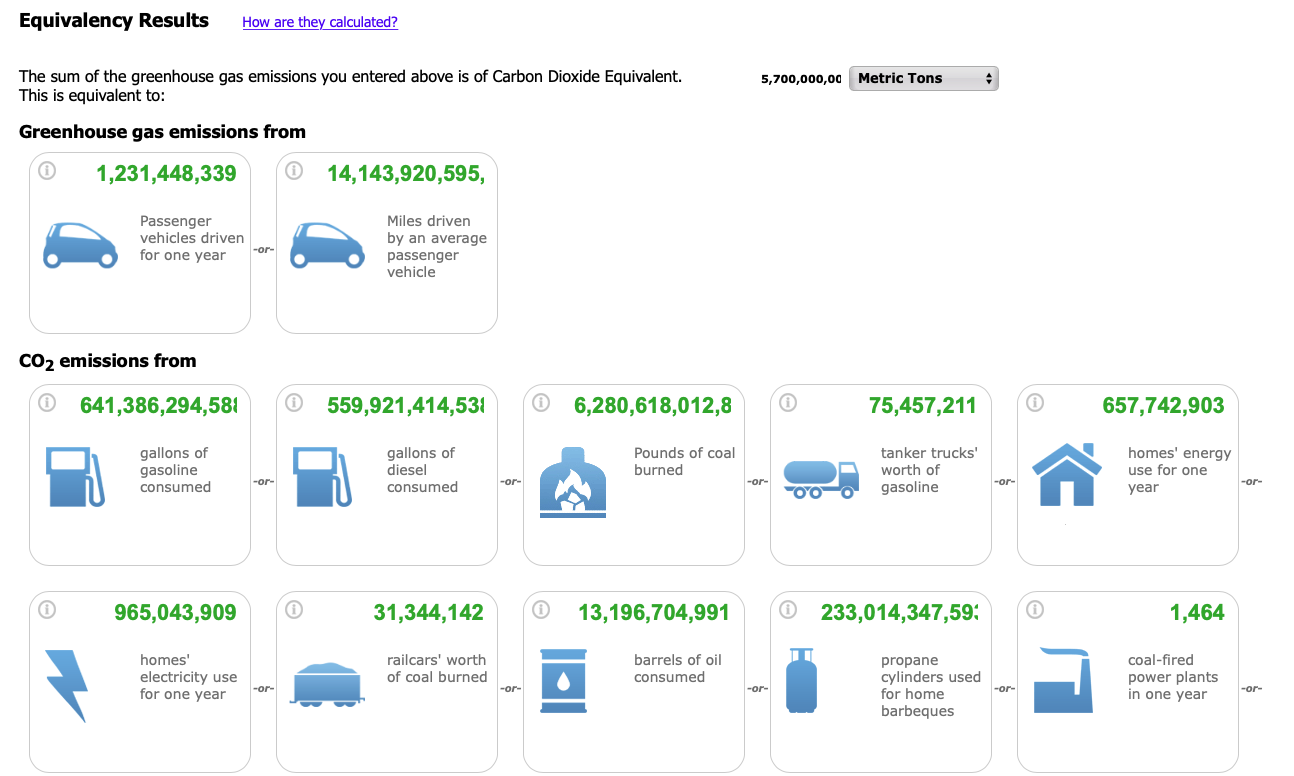

Apart from tropical rainforests, peatlands are another factor to consider in terms of palm oil cultivation. Like tropical rainforests, peatlands within palm oil-producing countries like Indonesia are carbon sinks, meaning they store massive amounts of carbon within the soil. Peat soils can account for even more carbon absorption, 18 to 28 times more than forests can (2). Natural carbon sinks prevent excess CO2 from being released into the atmosphere, are a significant component in reducing global warming (2). Southeast Asia, particularly Indonesia, contains 75% of the world’s tropical peat-soil carbon (2). If this quantity of peat-stored carbon were emitted into the atmosphere as C02, it would be equivalent to the total carbon emissions of approximately nine years of global fossil fuel use (2) The methods to plant oil palm trees require removal of excess water from the soil. The drainage of water from the soil results in the peat decomposing, causing CO2 emissions that can continue for decades after the soil is degraded and increases the peat’s potential fire risks (2). Slash-and-burn is an intentional method to clear large amounts of land for agricultural use and is highly destructive. Over the last few decades, some of the world’s largest wildfires have occurred on degraded peatlands, resulting in hundreds of years’ worth of stored up (sequestered) carbon being released into the atmosphere and causing continued burning for weeks to even months (2). These fires can also increase locals’ health risks since the continued burning creates smog, haze, and continued respiratory issues. One peatland wildfire in Indonesia that occurred in 1997 resulted in one single event emitting as much CO2 as the US released within an entire year (2). The US had 5.70 billion tonnes in annual CO2 emissions in 1997, comprising various fuel types use for energy, not including total land-use emissions (10). The total CO2 emissions in the US in 1997 are equivalent to 1,464 coal-fired power plants emitting CO2 in a single year (11).

Is there such thing as sustainable palm oil?

The Roundtable of Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO) was created in 2004 by a group consisting of retailers, banks, investors, and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) (12). Using groups such as the RSPO to certify or label products with sustainable palm oil is meant to ease consumer’s awareness of the environmental and ethical issues caused by palm oil production. RSPO certified companies are required to guarantee that the forests being assessed promote their high conservation values (HCVs) before starting a new planting cycle (12). Another critical component to new plantings is that these palm oil plantations must not be located in high carbon stock (HCS) areas, which is reinforced by the Palm Oil Innovation Group (POIG) (12). However, there is no such thing as “sustainable” palm oil, even if certified by the RSPO or other NGOs. A group of researchers led by Dr. Roberto Gatti collected evidence from multiple datasets over fifteen years to determine overall tree loss due to palm oil plantations in three countries in Southeast Asia - Indonesia, Malaysia, and Papua New Guinea (12). Gatti et al. had found that from 2001 to 2016, all three countries lost approximately 31 million hectares of tree cover, contributing to 11% of their total land area (12). The total amount of tree cover loss is roughly the same size as the entire state of Mississippi.

Within the same period, the total tree loss due to palm oil concessions was close to 6 million hectares, equivalent to 34.2% of the area covered by these properties (12). The years with the highest tree loss rates in all three countries due to palm oil concessions were 2009, 2012, 2014, and 2016 (12). Most of the RSPO certified concessions (total of 2,210) overlapped with areas with the highest amount of tree loss since 2011 (12). Gatti et al. had noticed an annual downward trend between 2006 to 2010, presumably due to the RSPO agreement in 2004, but there was another increase in annual tree loss after 2010 (12). The net loss was high, with a total of 750k hectares in a span of 15 years (41.5k ± 7.2 k ha/year on average from 2007 to 2016), representing 38.3% of tree loss in the areas owned by certified concessions (12). This is even higher than non-certified regions (34.2%). Gatti et al. had concluded that although there was a slight reduction in 2007 within RSPO concessions, the highest percentage of tree loss was within certified areas, confirming that “sustainable palm oil” is still associated with a significant amount of forest degradation (12). They also concluded that after 2007, the percentage of tree loss cover continued to be higher in certified areas and was still higher than in non-certified regions (12). There is no reason for these accredited companies to claim their products contain certified palm oil. In terms of deforestation between certified and non-certified concessions, there is no significant difference between the two. The method for oil palm plantations still requires total tree removal within tropical ecosystems. This shows that, unfortunately, there is no way to realistically produce “sustainable” palm oil that did not contribute to further deforestation. Most companies with a certified palm oil label are technically greenwashing consumers while continuing with a business-as-usual approach to their product production. Gatti explains that multinational companies have tried to manipulate consumers over the last two decades and find ways to continue business-as-usual motives with palm oil in their products while accommodating to the increasing pressures and concerns from environmental groups and consumers alike using greenwashing-based tactics as leverage (13).

Fig. 1: Map of total tree loss distribution in Southeast Asia showing comparisons in a span of 15 years (left panels) from 2001-2016 showing annual tree loss (right panels) in various sections (whole territory, palm oil non-certified concessions, and RSPO certified concessions). Credit: Cazzolla Gatti et al. 2019.

Fig 2: Total tree loss within 2001-2016, showing difference in area types (RSPO concessions, non-certified concessions, and total area) within Indonesia, Malaysia, and Papua New Guinea. Credit: Cazzolla Gatti et al. 2019.

What can we do?

The most common approach is to search for similar products that do not contain palm oil and are supplemented by other vegetable oils. Bring awareness to smaller companies that may use palm oil in their products but may not realize the negative impacts of “sustainable” palm oil. For example, UK cosmetics company LUSH uses a combination of rapeseed oil and coconut oil instead of palm oil (15). There are some complications with other vegetable oils, in terms of environmental demands and other requirements to produce the vegetable oils, but overall they do not contribute to as much extreme carbon emissions and deforestation as palm oil does. It is important to note that there are over 200 names for palm oil ingredients. Some ways to avoid palm oil are:

Look at the ingredients before purchasing, there are many websites (one linked above) that can help you decipher if there is any palm oil found within a specific product.

Cheyenne Mountain Zoo has developed an app for scanning and looking up products to confirm if there is palm oil within the product. This is a very helpful tool that I use all the time when I’m out shopping.

Be aware of major corporations such as Nestle, Unilever, etc. typically most prepackaged food made by them contain palm oil.

If a product contains a high percentage of saturated fats (>40%) as the total fat content, it more than likely contains palm oil

Choose products that clearly label themselves as 100% sunflower oil, olive oil, coconut oil, etc.

Educate those around you! Explain the importance of understanding the ecological impact of palm oil. You as a consumer have the power to choose what you do and do not support!

References and other useful links:

Henson, Ian E. “A Brief History of the Oil Palm.” Palm Oil, 2012, pp. 1–29., doi:10.1016/b978-0-9818936-9-3.50004-6.

Palm Oil and Global Warming - Union of Concerned Scientists. www.ucsusa.org/sites/default/files/legacy/assets/documents/global_warming/palm-oil-and-global-warming.pdf.

Dumelin, Erich E. “The Environmental Impact of Palm Oil and Other Vegetable Oils.” Society of Chemical Industry Conference on 'Palm Oil - The Sustainable 21st Century Oil - Food, Fuel & Chemicals', 23 Mar. 2009, www.ukm.my/ipi/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/29.2009The-Environmental-Impact-of-Palm-Oil-and-Other-Vegetable-Oils.pdf.

“8 Things to Know about Palm Oil.” WWF, www.wwf.org.uk/updates/8-things-know-about-palm-oil.

Petrenko, Chelsea, et al. “Ecological Impacts of Palm Oil Expansion in Indonesia.” The International Council on Clean Transportation - White Paper, July 2016, theicct.org/sites/default/files/publications/Indonesia-palm-oil-expansion_ICCT_july2016.pdf.

Meijaard, Erik, et al. “The Environmental Impacts of Palm Oil in Context.” Nature Plants, vol. 6, 2020, pp. 1418–1426., doi:10.31223/osf.io/e69bz.

Sheil, Douglas, et al. “The Impacts and Opportunities of Oil Palm in Southeast Asia - What Do We Know and What Do We Need to Know?” World Agro Forestry, 2009, apps.worldagroforestry.org/downloads/Publications/PDFS/OP16401.pdf.

“Palm Oil PRICE Today | Palm Oil Spot Price Chart | Live Price of Palm Oil per Ounce | Markets Insider.” Business Insider, Business Insider, markets.businessinsider.com/commodities/palm-oil-price.

Shahbandeh, M. “Palm Oil Usage Worldwide 2020/2021.” Statista, 26 Jan. 2021, www.statista.com/statistics/274127/world-palm-oil-usage-distribution/.

Ritchie, Hannah, and Max Roser. “United States: CO2 Country Profile.” Our World in Data, 11 June 2020, ourworldindata.org/co2/country/united-states.

“Greenhouse Gas Equivalencies Calculator.” EPA, Environmental Protection Agency, 15 Oct. 2018, www.epa.gov/energy/greenhouse-gas-equivalencies-calculator.

Cazzolla Gatti, Roberto, et al. “Sustainable Palm Oil May Not Be so Sustainable.” Science of The Total Environment, vol. 652, 2019, pp. 48–51., doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.10.222.

Dalton, Jane. “No Such Thing as Sustainable Palm Oil – 'Certified' Can Destroy Even More Wildlife, Say Scientists.” The Independent, Independent Digital News and Media, 15 Dec. 2018, www.independent.co.uk/climate-change/news/palm-oil-sustainable-certified-plantations-orangutans-indonesia-southeast-asia-greenwashing-purdue-a8674681.html.

Tullis , Paul. “How the World Got Hooked on Palm Oil.” The Guardian, Guardian News and Media, 19 Feb. 2019, www.theguardian.com/news/2019/feb/19/palm-oil-ingredient-biscuits-shampoo-environmental.

Swain, Frank. “How Do We Go Palm Oil Free?” BBC Future, BBC, www.bbc.com/future/article/20200109-what-are-the-alternatives-to-palm-oil.

Jong, Hans Nicolas. “'Meaningless Certification': Study Makes the Case against 'Sustainable' Palm Oil.” Mongabay Environmental News, 13 Aug. 2020, news.mongabay.com/2020/08/palm-oil-certification-sustainable-rspo-deforestation-habitat-study/.

Gaiam. “6 Ways to Avoid Palm Oil (and Why You Should).” Gaiam, www.gaiam.com/blogs/discover/6-ways-to-avoid-palm-oil-and-why-you-should.